Gili Tal 'Agonisers'

-

selected works

View: ,

'Benevolence/malevolence'

fridge, coca cola cans, other fridge contents 2015

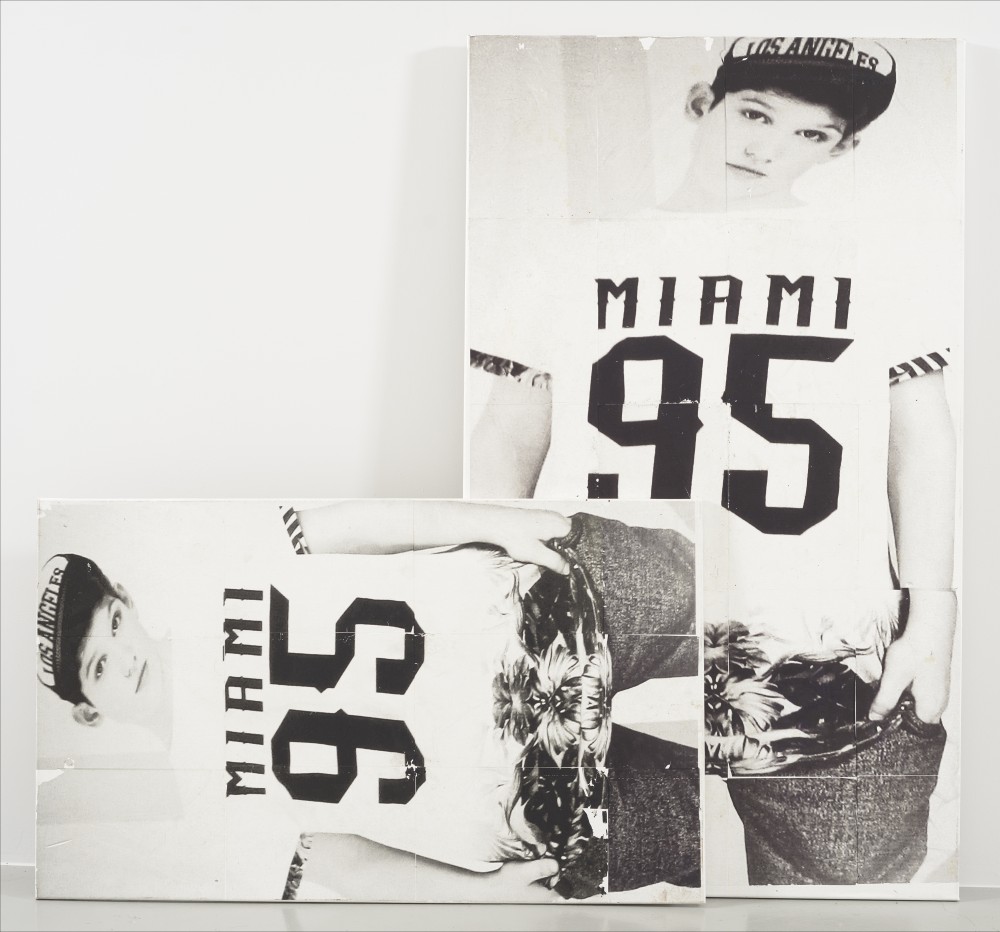

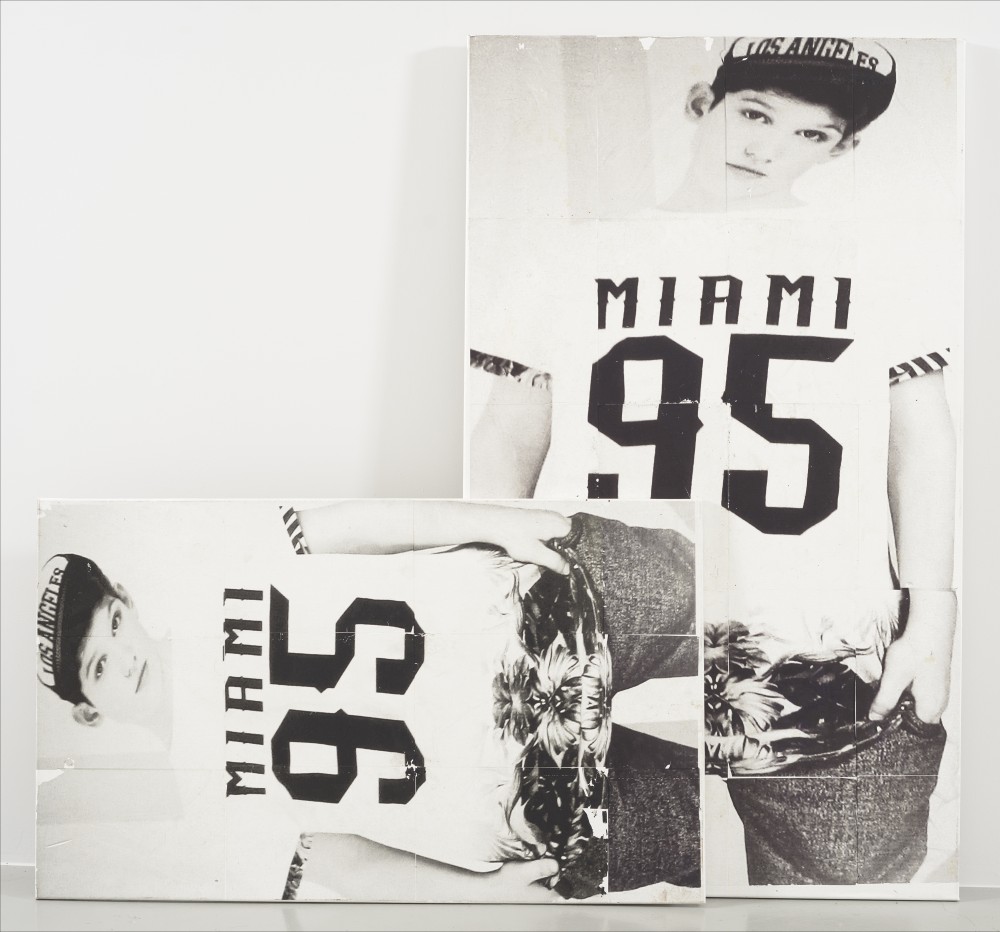

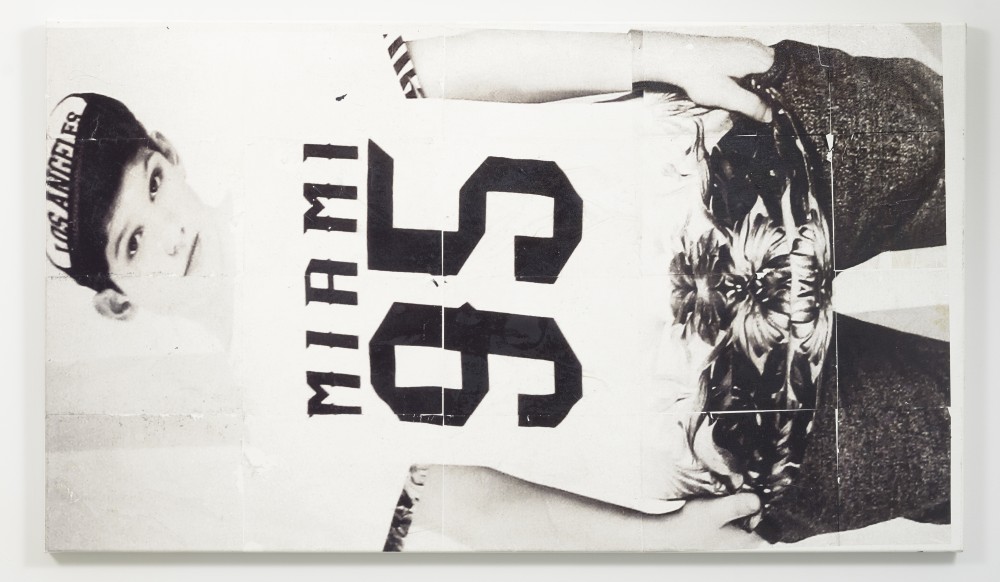

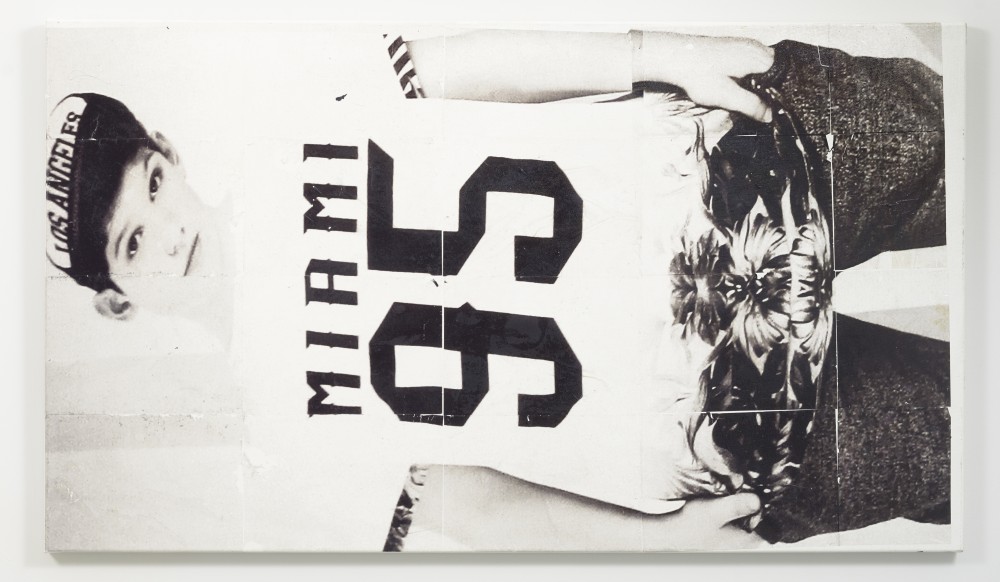

'Flâneur ‘95'

Lazertran and oil on canvas 135×100cm 2015

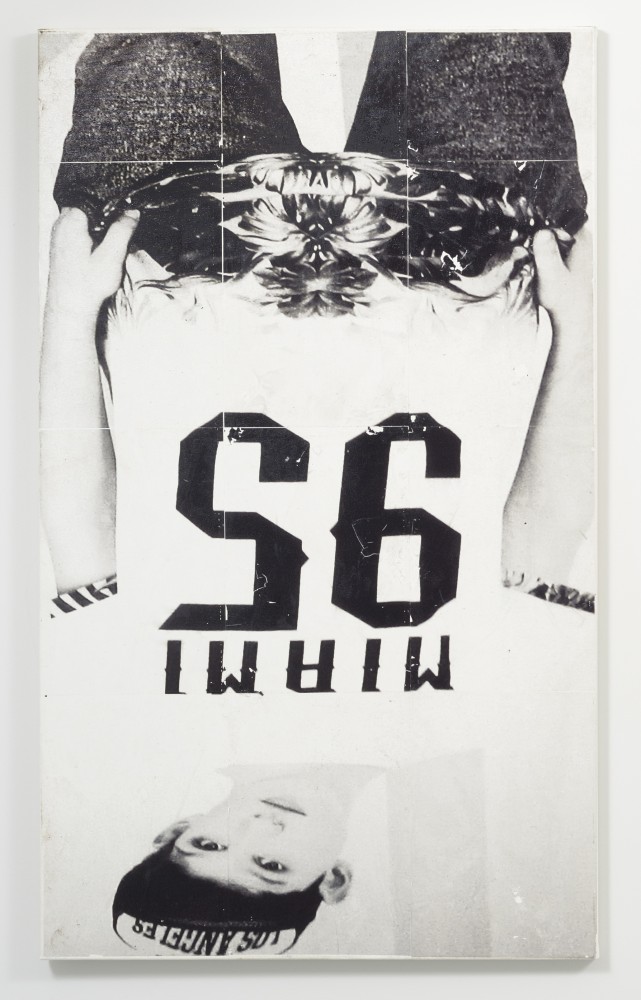

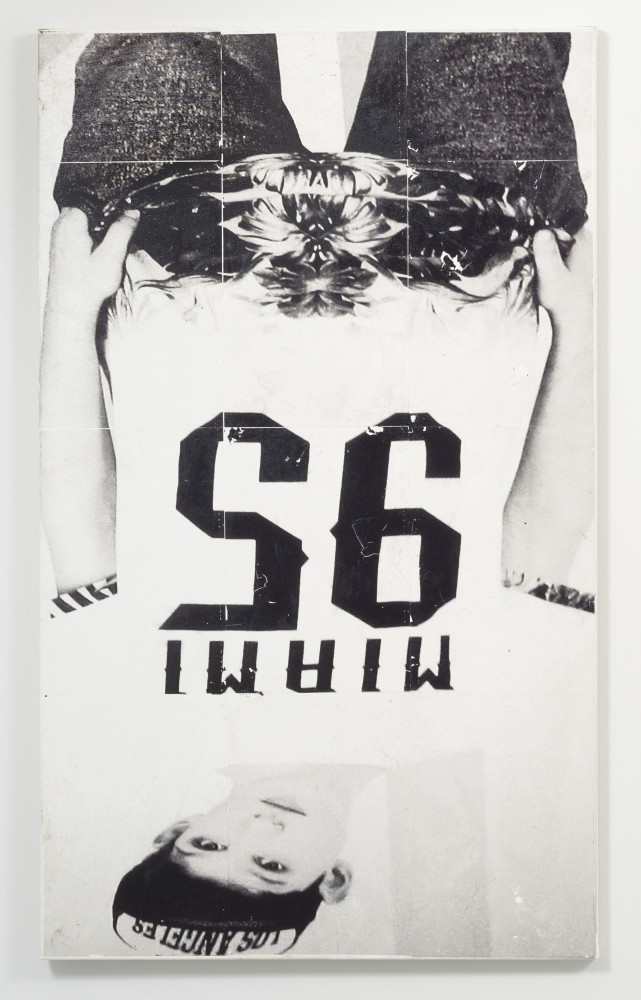

'Flâneur ‘69'

lazertran and oil on canvas 100×60cm 2015

'Flâneur ‘69'

lazertran and oil on canvas 75×135cm 2015

'Agoniser 1 (Love and War) & Agoniser 2 (But the World Keeps on Turning)'

monitors, dvd players, DVD, industrial entrance mat 2015

installation views

View: ,In his ‘Critique of Everyday Life’, Henry Lefebvre writes of:

‘Intense instants - it is as if they are seeking to shatter the everydayness trapped in generalized exchange. On the one hand, they affix the chain of equivalents to lived experience and daily life. On the other, they detach and shatter it. In the ‘micro’, conflicts between these elements and the chains of equivalence are continually arising. Yet the ‘macro’, the pressure of the market and exchange, is forever limiting these conflicts and restoring order. At certain periods, people have looked to these moments to transform existence.’ [1]

As media and political powers increase in centralisation and control, everything around them dilapidates in near perfect reciprocity. At the same time, the reality of this experience is continually subdued by the promise of immediate or virtual presence elsewhere or by identification with a different period in time. The vital elsewhere seems most effective as possibility, as image idea, as a moment of frisson. There is a cyclical relationship between the material world and its romanticisation that often works on a tragic / euphoric order. Even the most tired iteration of, say, Americana (as seemingly mythical signifier of a period ending with the break up of the Breton Woods agreement in the early 1970s and the consequent slide to neoliberalism) is still affective in giving rise to an imagination of urban living that alters in turn the appearance of Poplar, 2015. In literature the figure of the flâneur embodies one way of achieving transformation. The flâneur wanders round the city floating from salon to café, amusing himself and making discoveries, experiencing the city as if it were the substance of a dream. Since love is the conquest of discontinuity between individuals, there is an erotic dimension to this “losing oneself” in the crowd, or in the city. In a varying light, Marx also referred to this when he stated in the Grundrisse that Capital must “strive to tear down every spatial barrier to intercourse, i.e., to exchange, and conquer the whole earth for its market”, and it seems true that for at least three decades now the invocation of the flaneur, as agent, has led not so much to timeless experiential drift (nevermind the production of revolutionary spaces) as to what is euphemistically named regeneration. [1] Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life, Volume 3, trans. Gregory Elliot (London/New York: Verso, 1991), p. 57.